Baji Rao I – one of India’s greatest warriors – has swept into public consciousness after ‘Bajirao Mastani’, a movie that celebrates his passionate love for the beautiful Muslim courtesan, Mastani, whom he married against all opposition. Yet, few remember the fact that he was a master of maneuver warfare, a general who carried Shivaji’s legacy, (See ‘Gad Aala, pan Sinh gela – The Capture of Sinhgarh fort), and helped consolidate the Maratha Empire. He remained undefeated in forty battles and the secret of his victories was simple. He travelled light, moved fast, hit the enemy where least expected, and then disappear to surface elsewhere.

Baji Rao I took over as the second Maratha Peshwa (Prime Minister) after his father Balaji Vishwanath died in 1720. He was just twenty at that time, and his appointment as Peshwa by Chhatrapati Shaju, met with much resentment from the elders of the court who eyed the coveted position. Yet, as time would prove, Shaju’s choice was wise. Baji Rao took the Maratha Empire to great heights even reaching the doorsteps of Delhi.

In his twenty years as Peshwa, he re-developed the Maratha Army on the concept of nimble, fast moving cavalry that travelled light, with no excess baggage whatsoever. They lived sparsely, carrying just enough to sustain them for the campaign. Each man had a cloth pouch containing two half-baked chappatis, a packet of salt, a handful of parched gram, two or three chilies, an onion and maybe a lump of jaggery. These were the standard daily rations for each man, General to Sowar alike. The army had no encumbrances, no camp followers or baggage trains and moved fast on their nimble Deccan ponies – three between every two horsemen – appeared out of nowhere, struck hard and retreated. Following the classical tenets of maneuver warfare they extended the Maratha Empire not only across the Deccan, but northwards into Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat.

Maratha Horseman

Baji Rao’s campaigns were studied by General Montgomery who applied the same principles in his tank battles two and a half centuries later. The battle that most aptly brings out his skillful use of maneuver is the Battle of Palkhed, in which he encircled and defeated the much superior army of the Governor of Mughal Deccan and forced him to surrender virtually without a fight.

The Battle of Palkhed

The fledging Maratha Empire had taken root under Shivaji, but had fallen into disarray after his death in 1680. Shivaji’s son, Sambhaji was tortured and killed by Aurangzeb, and his grandson Shaju imprisoned in Delhi to curb any future Maratha ambitions. Shaju’s escape after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, began the revival of the Maratha Empire.

Shaju was appointed ‘Chhatrapati’ – the Emperor – and guided by able Peshwas, first Balaji Rao and then Baji Rao I – the Maratha Empire began rebuilding. They were granted a right by the Mughal Emperor to claim Chauth (or one fourth) and Sardeshmukhi (a 10% surcharge) in the areas controlled by them. This included the six provinces of the Deccan; Aurangabad, Ahmadnagar, Berar, Khandesh, Golcunda and Bijapur.

The rise of the Marathas was viewed as a direct threat to Nizam ul Mulk, the Governor of Mughal Deccan. The Maratha claims of Chauth and Sardeshmukhi was a blow to his own power and revenues. In December 1726, he set out with a large army comprising of around 80,000 cavalry and infantry and over 100 heavy guns and cannons. In August 1727, he burst through Northern Maharashtra and entered Maratha territory.

At that time, Baji Rao was campaigning in Karnataka with the bulk of the Maratha Army. He was hastily recalled by Chhatrapati Shaju to counter the threat. He reached Pune in mid-Oct 1727 and immediately moved northward towards Ahmadnagar towards the border between the Nizam’s and Maratha territory.

The Nizam was waiting for Baji Rao in the area between Ahmadnagar and Aurangabad. In those open plains, his large army and heavy artillery would have a distinct edge in close battle. Yet, rather than engage the Nizam’s army, Baji Rao bypassed it and entered the Nizam’s territory, first attacking the town of Jalna, 40 kilometers away. He then moved to Washim, another 30 kilometers ahead, then Mangilpur and Hathgam – and ransacked the area. From here, he made an obvious and deliberate move towards Burhanpur;, the most prosperous town of the Mughal Deccan, forcing the Nizam to move to counter him. But the Nizam’s ponderous army, weighed down by his heavy guns and a vast administrative train, could not keep pace with Baji Rao’s fast paced maneuvers. As the Nizam’s army approached, Baji Rao moved further westwards towards Gujarat, crossing the Tapi River and then the Narmada and moved towards Bharuch to threaten the Mughal ports in Gujarat.

Over the next three months, from October to Dec 1727 Baji Rao moved from place to place. He knew he could not counter the Nizam’s much superior army in a pitched battle and wanted to exhaust him by making him follow his maneuvers. By crossing rivers repeatedly, he hoped to force the Nizam to shed his heavy guns – which could not make a river crossing easily. And he refused to engage his opponent in a pitched battle, choosing instead to exhaust him and then lure him to a place where his own mobility could be best exploited.

The Nizam himself changed his strategy and in January 1728, he turned south towards Pune, the principal Maratha town. He surrounded the town and forced Chattrapati Shaju to take refuge in Purandar fort. He also used the internal rift between the Marathas by placing Shahu’s cousin, Sambhaji of Kolhapur on the Maratha throne. He gambled that this threat to Pune and the seat of Maratha power would force Baji Rao to reverse his steps and draw him to battle in the open area around Pune.

Baji Rao did not take the bait. Rather, he turned towards Aurangabad – the greatest city of Mughal Deccan named after Aurangzeb himself. By mid-February he was prowling the outskirts of Aurangabad and Burhanpur. It was a war of nerves as both sides threatened the cities of their opponent, and the Nizam cracked first. He withdrew from Pune and rushed to counter the threat to Aurangabad. He moved with as much speed as he could muster towards Palkhed where the Maratha army was deployed.

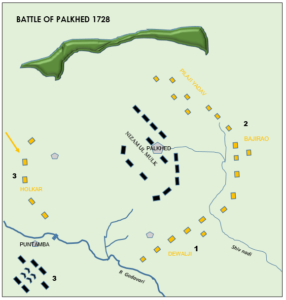

To reach Palkhed, the Nizam’s Army had to cross the Godavari River at a place called Puntambe. An advance guard crossed over the river first on 25 February first and selected a camp site. They were followed by Banjara civilian traders who accompanied the army and set up a bazaar to sell supplies and provisions. After them would come the main army and finally the heavy guns and rear guard.

By the time the Nizam’s advance guard crossed the Godavari and reached Palkhed, Baji Rao had already deployed his forces around the village in a horseshoe formation. His force of around 25 -30,000 cavalry were led by Malhar Rao Holkar, Ranoji Shinde, Pawar and other seasoned generals. In a series of skirmishes they defeated the Advance Guard, and also routed the Banjara traders forcing them to flee, leaving their supplies behind.

Hearing of the encounter, the Nizam crossed the Godavari with his main body. However, to gain speed he had to leave behind all his guns and heavy equipment – just what Baji Rao wanted him to do. As the main body moved towards Palkhed, Baji Rao sent his cavalry on their flanks and rear. A strong detachment also blocked the way to the Shiv Nala in the North which was their only source of drinking water. Maratha cavalry patrolled around the Nizam’s vast army, cutting them off from their supplies and drinking water. Baji Rao was in the center with the bulk of his forces, blocking the route to Aurangabad. One wing of Maratha cavalry blocked the Godavari River ensuring that their guns could not cross. The Nizam was without his most potent weapon as his guns remained powerless and impotent on the other side of the river.

Encircled and hemmed in from all sides, the Nizam was unable to fight or maneuver. Fast running out of water and supplies and losing men in daily skirmishes with fast moving Maratha raiding parties, he finally capitulated on 28 February. On 6 March 1728, he signed the Treaty of Moongi- Paithan in which he agreed to return all the territories his armies had overrun. He also agreed to allow them to collect chauth and sardeshmukhi over all his territories in the Deccan, thus acceding to the Marathas’ main demand.

The Marathas had overcome a force almost thrice their size, through a series of maneuvers and with hardly any fighting. Throughout the campaign, Baji Rao resisted Shaju’s entreaties to go on the defensive, insisting that, “To cut a tree, you do not need to cut off the branches and trunks – the best way is to strike at the roots.” He struck when the time was right, and lopped off the very roots of Mughal power in the Deccan.

In 1737, the Nizam tried again to destroy Maratha power. His vast army of 80,000 men were encircled and trapped around Bhopal – in a battle which was a virtual re-run of Palkhed.

Palkhed was just one of Baji Rao’s battles. Using the same principles of mobility, he expanded the Maratha kingdom across the Deccan and Malwa. He had promised to take Maratha power up to Attock, but it was a promise he could not keep. On 28 April 1748, at the age of just forty, he died on the banks of the Narmada River, after a sudden fever, most probably brought about by a sun stroke. He died as he had lived, out in the open with his men in the midst of another campaign.

In twenty years, Baji Rao fought 40 battles, remaining undefeated in each. His key to success was simple, move light and fast. It is ironic that the Marathas would forget these very tenets. His wife Kashibai, had been deeply hurt by his love and marriage to Mastani, (Baji Rao was given the hand of the beautiful Mastani while out on a campaign. His passionate love for the Muslim courtesan and marriage to her, scandalized and enraged Maratha society.) After his death, she passed a decree stating that in future, Maratha soldiers would be permitted to take their families with them – so that they would not get beguiled by other women when out on long campaigns. That decree had fateful consequences. The Maratha Army now became encumbered with women and children and they would lose their greatest asset – their mobility and speed. Just sixteen years after his death, a Maratha Army – slowed down with over around 30,000 women and children would meet a crushing defeat in the Third Battle of Panipat (See 14 January 1761 – ‘The Blackest Day in Indian History.) The Maratha Empire was established and consolidated on the principles of speed and mobility. When they lost sight of these principles, they began their decline.