One of the advantages of winning battles is that the victor gets to write its history. Unfortunately Indian rulers have won few of their battles and the versions we receive of them are from other sources. When the British won at Palashi, they even changed the name to an Anglicized version. This momentous battle has thus gone down in history as the Battle of Plassey, one which helped establish Imperial rule in India.

The East India Company made inroads into India by the mid-18th Century. They successfully ousted the French, the Dutch and Portuguese in the Carnatic Wars of 1850s and became the largest trading power of Peninsular India. As their power grew, so did their ambitions and they turned their eyes on Bengal, India’s richest province.

Bengal was ruled by the 19 year old Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah, a young inexperienced prince who had been abruptly thrust on the throne after the death of his father. Yet, he proved to be surprisingly firm. The East India Company has established settlements in Hoogly and Calcutta and had slowly secured a monopoly of all trade, even refusing to pay taxes and tariffs to the state. Siraj-ud-Daula clamped down on their depredations, made them stop building fortifications, refused to grant them any further concessions, and earned their ire.

As the tensions were building up, the British under Robert Clive, were making plans to remove him. They had got in touch with his Commander in Chief, Mir Jafar promising to put him on the throne if he agreed to help them. Mir Jafar – whose name has since then been synonymous with treachery – agreed willingly and also roped in two senior commander, Rai Durlabh and Yar Latuf Khan with him. The trio promised Clive that they would take no part in the battle and help in the defeat of their Nawab.

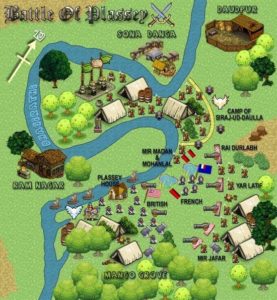

The young monarch was unaware of these machinations when he marched out of his capital of Murshidabad in mid-June with a force of around 35,000 infantry, 18000 Cavalry and 50 pieces of excellent French manned artillery. Clive too left Calcutta with 600 European and some 2400 native soldiers and a small artillery park of six field guns and two small howitzers. His plan to defeat a force almost ten times his size hinged on the fact that Mir Jafar, Yar Latuf Khan and Rai Durlabh had been won over and would defect at a crucial stage of the battle.

Clive’s force reached Palashi, a small village on the banks of the Baghirathi River around midnight on night 22 June. He deployed his forces in a large mango grove with his guns ahead in a brick kiln from where they could fire effectively. Around three kilometers away Siraj-ud-Daulah’s vast, if disunited army, were encamped and sounds of singing and music wafted over from their camp. The next morning, 23 June 1757, his army moved out and formed a large crescent shaped deployment around the British force (See map). The traitors with their divisions were in the South flank and Siraj- ud-Daulah with his one loyal General Mir Mardan, were in the North. As events would show, the Southern flank took no part in the battle, and it was only Mir Mardan and his division that fought.

At around 8 in the morning, the battle began with a furious cannonading from each side. Both sides launched tentative attacks which could not move forward because of enemy fire. By around noon it seemed a stalemate was emerging and then something happened that dramatically changed the situation.

It began to rain.

It should not have been such an unexpected situation. After all it was mid-June when the monsoons traditionally erupts over North India. But with inexcusable negligence, the Nawab’s gunners had forgotten to carry tarpaulins to cover their weaponry. In the torrential downpour, the gunpowder got wet and their cannons were rendered ineffective, unable to fire.

Tarpaulins enabled the British to fire in spite of rain

When the rain stopped an hour later, the Nawab’s only loyal general Mir Mardan, launched his attack, thinking that the British guns would be similarly affected. The British had covered their guns – their gunpowder was dry. The attack was met with musket and cannon fire, but with Mir Mardan himself leading the charge, the attack pressed on and came dangerously close to the British positions in the grove.

Then came the turning point of the battle. Mir Jafar, Rai Durlabh and Yar Latuf Khan had not moved their divisions and Siraj-ud-Daulah himself came to Mir Jafar’s tent pleading him to move. Rather than support his monarch, Mir Jafar actually proposed that Mir Mardan’s attack be halted and they would launch a coordinated assault the next morning. The inexperienced Nawab gave in and ordered Mir Mardan to halt his attack and move back to the camp.

The order caused nothing but confusion. His troops which were closing in began withdrawing and Mir Mardan himself was killed. The withdrawal became a retreat and then a rout with British guns taking a heavy toll and their own guns unable to provide covering fire. Mir Jafar also passed message to Clive about what he had done, and seizing the moment, the British attacked, pursuing the troops back their camp. Throughout the battle, the traitors with their three divisions of around 45,000 men stood impassively watching the defeat of their comrades which they had helped engineer.

By nightfall, Clive and his men had taken over Siraj-ud-Daulah’s camp, routing his troops. Siraj-ud-Daulah fled on camel back towards Murshidabad, but was overtaken and brutally put to death on the orders of Mir Jafar. Mir Jafar himself met Clive the next morning who greeted him with, “Hail, Mir Jafar, Emperor of Bengal, Orissa and Bihar” and presented the new Nawab with a ceremonial tray of gold coins. The British had succeeded in putting their own puppet on the throne.

Mir Jafar became the Nawab of Bengal and allowed the British to loot India’s richest province dry. Their victory at Palashi gave them a grip which allowed them to continue their depredations across the country. More than that, it established a psychological supremacy that lasted generations. But it was not British supremacy that won them the battle. It was the treachery and deceit of our own.

And the fact that they forgot to carry tarpaulins for their guns.