This battle goes so back in time, that no one knows the exact date. The Battle of Hydaspes, between Alexandra and King Porus took place sometime in Mid-May 326 BC according to Greek historians. Indian sources, who call it the Battle of Jhelum River, put in sometime in the monsoon of 326 BC (which can be anytime from June to October). While the exact date of the battle is lost in antiquity, its impact is not.

The story began when Alexandra, the greatest conquering hero in history marched across Europe and Asia in his attempt to conquer the very end of the earth. He crossed the Hindu Kush Mountains in late 327 BC and entered the Indian sub-continent. India then was string of independent kingdoms perpetually warring with each other. Most of the border states in present day Afghanistan and Pakistan were easily subjugated easily. Others capitulated without a fight. The Raja of Taxila also gave him his beautiful daughter as a wife, with 30 elephants as dowry.

Yet Porus, the 6 and a half foot tall monarch of the Paurava kingdom between the Jhelum and Beas Rivers refused to accede to Alexandra and chose to fight. He made his stand on the banks of the Jhelum River in what is the first recorded battle between an Indian ruler and a foreign invader.

It is strange that the name of this Indian hero has been lost in time. It was the king of Pauravas who fought Alexandra – and not a man named Porus. Porus was the name given to him by the Greeks. And that unfortunately it is also the name history remembers him by.

Porus Alexandra

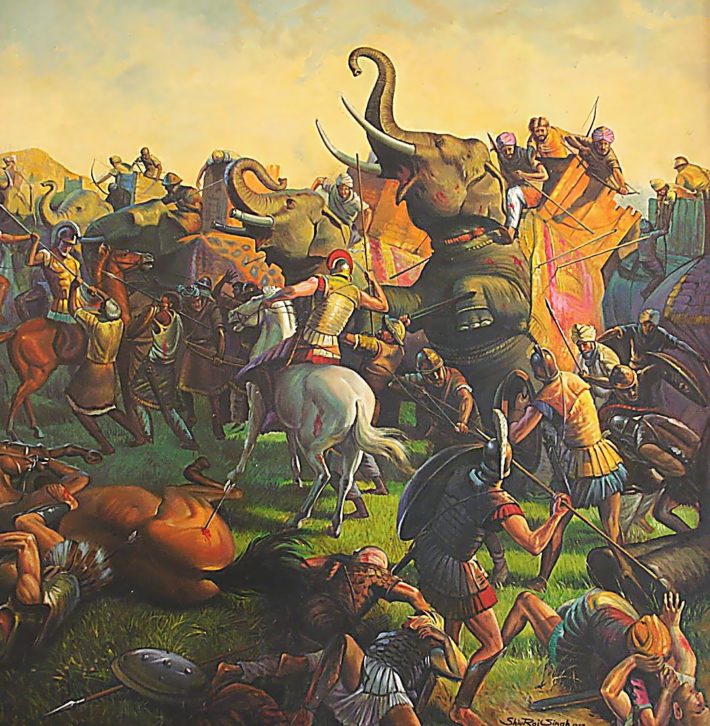

Porus’s army of around 20-25,000 infantry, 2500 cavalry, 600 chariots and 150 elephants was camped and waiting for Alexandra across the Jhelum River, which marked the borders of Porus’s kingdom. The Greeks army was centered around a force of around 15,000 excellent Cavalry and around 1,20,000 archers and infantry. This was a battle hardened army which had conquered half the known world and had perfected the concepts of fire and maneuver. The Greeks definitely held a clear edge in both numbers and quality.

The two armies faced off across the Jhelum for over a month. The Jhelum was in flood and Porus occupied its only crossing place. Unable to cross, Alexandra send his scouting parties along the river and one of them discovered a site twenty kilometers upstream. Here a small island in the middle of the swollen river, named Adnana , would enable them to get across. It would be a dangerous crossing, but it was a gamble that Alexandra was willing to take.

On the night of a violent thunder storm, Alexandra moved out with 13,000 of his Macedonian cavalry and Scythian archers towards Adnana, taking a wide circuit to avoid detection. The rest of his army remained in camp, with the campfires burning and the hustle of activity still depicted. Alexandra’s force reached Adnana and around midnight began the crossing, some on improvised rafts and boats, most swimming across on their horses. Over 200 were swept away in the fast flowing waters, but by morning the force was across and had established a Phalanx on the other side.

The Greek Phalanx consisted of a tight formation of Infantry with large overlapping shields to provide tortoise like protection. Each man was armed with a sarissa, a 24 foot long spear to impale a charging horse or man. On the sides were archers and to the rear were the Cavalry. It was a time tested formation, which would hold the enemy ahead of the Phalanx while the cavalry swooped down from the flanks to launch the coup de grace.

The Greek Phalanx

Porus scouts relayed the news of Alexandra’s crossing and he sent a covering force under his eldest son to counter it. The chariot borne encountered the Greeks in the area of the Karri plain, a flat open ground, in which their chariots got struck in the wet, swampy soil and were then decimated by Greek archers and cavalry.

With his Advance Force easily defeated, Porus now moved his entire army to counter the threat on his flanks. His ponderous army moved slowly, reaching the Karri Plain where Alexandra’s army were deployed. The first clash took place between the cavalry of the two forces, where the Greeks simply out-maneuvered them from their flanks. With his cavalry defeated, Porus now decided to attack the Greek lines frontally, using his elephants as a battering ram in the concepts of the time.

The Greek Phalanx had never been broken in any of their earlier battles, but then neither had they faced elephants before. Yet Alexandra had studied elephants and their habits carefully (thanks to the dowry of elephants he had received from the king of Taxila) and changed tactics to counter them. Instead making his Phalanx in a solid wall, he now deployed them in files with gaps of 8-10 feet in between. The charging elephants would thus be funneled into the gaps from where they could be attacked on to their vulnerable sides and rear.

From Greek accounts, the Indian attack was one of the most violent and determined assaults they had faced. Yet unknown to Porus, another element of the Greek army – a 10,000 strong force under General Meleager had also crossed the river during the battle and were now behind them and attacked Porus’ forces from the rear. Hemmed in by the phalanx in front and Greek cavalry behind them, Porus decided to make one last charge on the Greek ranks.

Porus led this attack himself and the force of the assault broke the Greek Phalanx – the first time it had ever been broken. For the next two hours or so fierce hand-to hand fighting raged with immense casualties to both sides. Finally, Alexandra sent an emissary to Porus, proposing a truce. Porus who had been wounded and had his elephant killed beneath him and was fighting a fierce dismounted action and responded to the emissary’s offer with a hurled javelin. Finally Alexandra himself approached him and after offering his condolences for the loss of both his sons in the battle, proposed a truce to halt further bloodshed. Porus finally accepted and when asked how he would like to be treated, gave the classical reply, “As a king would another king.”

The truce was called around four or five in the evening, but the drama was not over. As the armies were regrouping, collecting their dead and attending to the wounded, Alexandra’s force in the camp on the other side of the river, crossed over, and not aware of the truce, attacked the Indians from the rear, causing over 2000 casualties till order was restored. Both armies withdrew and licked their wounds and Alexandra made his plans for further inroads into India to reach the end of the world, which he was convinced lay across it.

This was not to be. His armies, tired and dispirited in the battle with “the most formidable foe we have faced” (as per the Greek historian Plutarch) and fearful of even more formidable foes ahead, refused to move further. At the banks of the Beas River, they mutinied, forcing Alexandra to begin his long journey across his conquered territories back to Greece.

In the first recorded battle with a foreign invader, the Indian armies had acquitted themselves well as valiant individual fighters, but not as a cohesive collective force. That trend would continue throughout the centuries as a stream of invaders invaded India. Indian armies would fight valiantly, but eventually individual skill and valour would prove no match for new concepts and technologies that the invaders brought in their wake. And the outcomes of each battle would be distressingly the same.