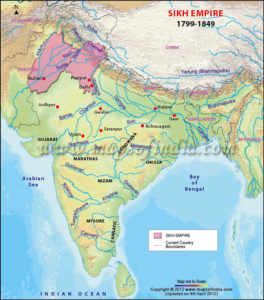

In the early years of the 19th Century, the Sikh Empire under Maharaja Ranjit Singh had expanded rapidly covering most of Western Punjab (modern day Pakistan) as far as Afghanistan. Its rise had unnerved the East India Company which had by then taken over most of North India. Punjab with its riches still remained out of their reach.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh Sikh Empire at its Prime

However, with the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1839, his stately court descended into petty squabbling. Numerous claimants arose for the throne and finally Jind Kaur, his youngest widow took over as Regent on behalf of his son, Dilip Singh. Others also vied for power. One was Lal Singh, the vizier, and Tej Singh, the Commander of the Army. Both aspired for the throne and it was in their interest to weaken the Empire, and especially the army which was getting increasingly assertive and emerging as an independent power center in itself. Many historians feel that Lal Singh and Tej Singh conspired the defeat of the Sikh Army to weaken Jind Kaur and promote their own interests. They had been in secret talks with the British and were continually passing inside information of the State right from the days preceding the wars.

The British exploited the self-serving ambitions of Lal Singh and Tej Singh in much the same manner they had used Mir Jafar and the other traitors to defeat the Nawab of Awadh in the Battle of Buxar (See “Establishing Imperial Rule- The Battle of Buxar.) Seeing the dissensions in the Court, they moved up a strong force of around 15 – 20,000 troops from Ambala and Meerut towards Punjab. This augmented the division of around 7000 men already located at Ferozepur. With the movement of British troops towards their border, the Sikhs moved their own army of 22 – 25,000 troops and 192 prized guns towards the Sutluj, the River which marked the boundary between the Sikh and British Dominions. The two forces were evenly matched. What would tilt the scales would be the ineptitude and treachery of the Sikh Commanders.

The two armies faced off across the Sutluj River and on 11 December 1845, the Sikhs sent a small detachment across the river to occupy the village of Moran. ( As per Sikh accounts the village legitimately belonged to them and they were moving into their own territory.) This was the trigger of outbreak of hostilities and set off the first Anglo Sikh Wars.

Cannonading began across the river and both sides moved aggressively towards the other. The Sikhs made the first move and crossed the River in strength heading towards Ferozepur. A large division under Tej Singh closed in on Ferozepur but though the British division there was unprepared and exposed, Tej Singh did not attack – perhaps deliberately. This would be the first of the many blunders the commanders made. Another force under Lal Singh moved to engage the large British force which was advancing from Ambala under Sir Hugh Gough. The British force was encountered around 30 kilometres from Ferozepur, near the village of Mudki, where the first major battle of the war was fought. The Sikhs attacked the British which had encamped within the village on night 18 December. Sikh cavalry – their skilled Gorchurras (or horse riders) – charged from the flanks but the British force recovered and halted the attack by cannon fire. The British infantry then advanced towards the Sikh position at night – a unexpected move since usually no fighting took place after nightfall. Even though casualties were caused in the confused fighting, by around midnight the Sikhs were driven off from the village leaving behind their guns. It was a battle which they could have easily won. But their commander Lal Singh fled and though the leaderless Sikhs fought gallant individual actions, they could not match for the disciplined and well-coordinated British moves.

Sikh Infantry in Defense

Flush with their initial – and somewhat unexpected – victory at Mudki, the British advanced towards Ferozeshah on 21 December where the bulk of the Sikh army was deployed. They made contact in the morning but waited till additional troops joined them from Ferozepur around noon. Reinforced, they attacked the Sikh positions around 3.30 p m. Under cover of an intensive artillery barrage, three battalions of Bengal Infantry and one British Infantry battalion advanced towards the Sikh positions. Half the attacking force was wiped out, but by nightfall they succeeded in making a breach in the Sikh positions.

All night, fierce fighting raged around the village. It became a series of skirmishes as Sikh and East India Company soldiers fought hand-to-hand battles in the congested lanes of the village. When dawn broke they had captured most of Ferozeshah and the Sikhs were pushed out of their stronghold and 71 of their prized guns had been captured.

As the exhausted British were regrouping Tej Singh’s fresh army appeared on the horizon. An attack now would have wiped out the remnants of British and Bengal troops. General Hugh Gough was expecting to be defeated and even sent message to the rear to burn all official documents. That is when a quirk of fate occurred. With their artillery out of ammunition, a British officer ordered the Artillery train to move back to Ferozepur with a strong cavalry escort, to replenish. Tej Singh viewed this as an outflanking move being carried out by their cavalry and even though his troops were keen on attacking, ordered a general withdrawal. It was an inexplicable act, and reeked of treachery.

Battles of the Anglo-Sikh Wars

After their unexpected defeat at Ferozeshah, the Sikh army was demoralised. The actions of their commanders had not gone unnoticed. Maharani Jind Kaur came from Lahore to exhort her army and reportedly even flung her chunni at the commanders – an insult which implied that they should be wearing women’s clothing. The morale of the Sikh army was bolstered with the arrival of capable commanders such as Ranjodh Singh Majitha and Sham Singh Attariwala and they gradually prepared for a fresh offensive.

On 21 Jan 1846, the Sikhs crossed the Sutluj and established bridgeheads near Aliwal and Sabraon. Sikh cavalry began attacking British supply lines and made forays as far as Ludhiana. The Sikh bridgehead was around seven kilometres long along a ridge near the village of Aliwal, with the Sutluj just behind them. That protected their flanks but also reduced their space for manoeuvre. Realising the danger of the bridgehead, the British launched a concentrated attack on 28 Jan with an entire Cavalry Brigade. Two Indian and one British Cavalry Regiment (16 Lancers) charged towards the Sikh positions as artillery carried out an incessant barrage of fire. The Sikhs formed a square to meet the attack – the time-honoured tactic of countering a cavalry charge – but were overrun and forced to retreat. By the end of the day they were forced back across the Sutluj losing over 2000 men and 67 valuable guns.

With the Aliwal Bridgehead eliminated, the British turned their attention to Sabraon. The Sikh contingent at Sabraon was led by Sham Singh Attariwala – a respected veteran and a courageous general. Unfortunately the overall command still rested with Lal Singh and Tej Singh who were conspiring for the defeat of their own army. They were in touch with the British and passing on key information to them. The Sikh bridgehead was connected by a single pontoon bridge on the Sutluj. The river was in flood after three days of continual rain and the bridge was considerably weakened.

Battle of Sabroan

The British built up their forces before launching their attack on Sabraon. Another division arrived from Ludhiana. 35 Heavy howitzers were also brought up to pound the Sikh positions. Then on 10 Feb 1846, one division launched a feint attack from the left, while two divisions launched the main attack on the right of the bridgehead. Here the defences were of soft sand, lower and more vulnerable – information that had been helpfully provided by Lal Singh to the British. The intensive bombardment collapsed the fortifications and the British attack made an initial foothold. In spite of repeated counter attacks the British held on and through the breach Infantry and Cavalry poured in. The Sikhs fought bitterly, launching repeated counter attacks, but were forced to retreat. Tej Singh fled the battle field and ordered his guns on the other side of the Sutluj to fire on the Pontoon bridge – ostensibly to prevent the British from using it. As fleeing Sikhs were racing across the bridge to the safety of the other side, the bridge collapsed and 20,000 men were trapped on the other side.

The Sikhs, led by Sham Singh Attariwala fought on grimly to the death. Some tried to cross the river but were swept away. British guns lined on the flanks poured a relentless fire on them and by the end of the day over 10000 Sikh soldiers perished on the battlefield.

The next day the British crossed the Sutluj and by 13 Feb reached Lahore, the seat of the Sikh Empire. Here The Treaty of Lahore was signed in which the Sikhs were forced to concede the valuable territory between the Beas and Sutluj Rivers. They also had to pay an indemnity of 1.2 Million pounds and since they could not pay the amount Kashmir was taken from them.

It was a crushing defeat for the Sikh Empire and with it the last challenge to British rule in North India disappeared. Yet in April 1848, the resentment at the defeat and the harsh terms of surrender erupted again in the Second Anglo –Sikh Wars. Here in the battles of Ramnagar and Chillianwala, the Sikhs inflicted much damage on the British, but unfortunately lost the Battle of Gujarat which was the most decisive battle of the war. With this the Sikh Empire finally disintegrated. Maharaja Duleep Singh signed away his claims to the throne and Punjab was annexed by the East India Company. Area from Multan, Peshawar, Lahore, Ludhiana, Jullandhar and right up to Kashmir came under British yoke. The fabled Kohinoor diamond was carried away to England and became one of the jewels on Queen Victoria’s crown – and India became the prime jewel of the British Empire.

The Sikhs were acknowledged as the finest fighters the British had encountered and were gradually amalgamated in the East India Company. Ironically for all their ferocity in fighting the British, the Sikhs would be instrumental in helping them during the First War of Independence. Sikh battalions were used against the rebellious battalions of the Bengal Infantry – the same battalions which had fought them in the Anglo Sikh Wars. (See ‘The First Fires of Independence) Using this card, the British ensured their loyalty and with the time tested policy of divide-and-rule maintained their hold on India for over a hundred years more.